Today, FTC staff released initial insights from the Surveillance Pricing 6(b) study, highlighting findings that intermediaries have access to a wide swath of data types and data sources (including direct consumer data, inferred data, and first- or third-party sources) to power tools that can influence the price a consumer or audience sees. While there is still much more work to do, the agency continues to proactively learn from and engage participants on surveillance pricing and how it may be affecting consumers and competition.

For decades, academics and researchers have been exploring how companies use data to impact the prices or discounts that a consumer sees. In addition, techniques used for targeting advertisements can potentially be used to target prices to individuals or groups.

Tracing some roots of information markets and early data brokers.

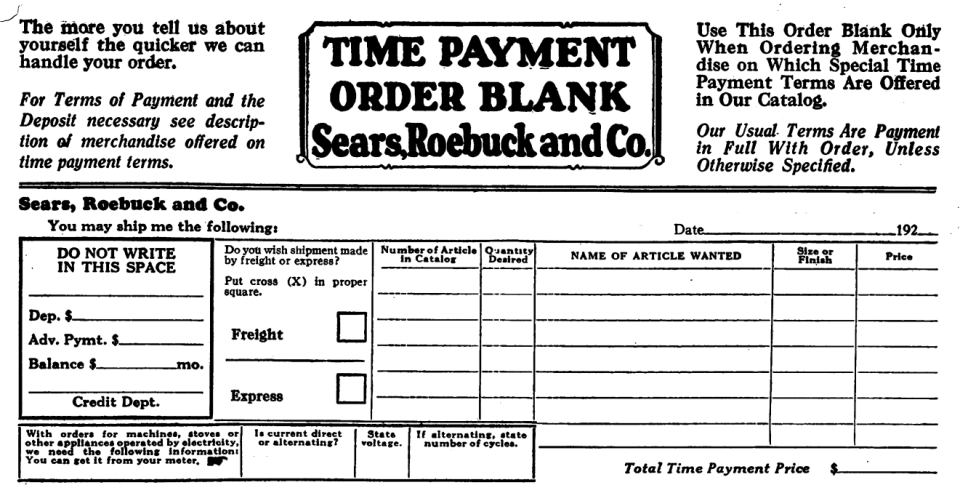

In the early twentieth century, the mail-order catalog, an atlas of endless consumer products, represented both the promise of American opportunity and the impacts of a corporate machine bringing mass market capitalism to people's front doorsteps. Starting as early as 1872, American department stores Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck & Co. have been credited with pioneering direct mail campaigns. To order from their catalog, a customer needed only to send their name, address, and items to be purchased to the sellers—an approach that not only collected customer data for each of their distribution lists through incentivizing sharing, but also bolstered these stores' appeal among Black customers, who were frequently subject to higher prices or other forms of racism from local store clerks.

By the late 1930s and 1940s, the popularity of direct mail marketing gave rise to a new kind of data-collecting enterprise: mailing list houses. These companies sprung up for the purpose of creating and selling lists of potential customer information, details, and addresses to retailers. Like modern day data brokers, the mailing list companies sold lists with a surprising degree of specificity. “Do you want to contact a list of left-handed golfers, dentists, ministers? Brokers will rent you their names,” reads a 1944 article on the companies in The Saturday Evening Post.

Calling to mind recent FTC actions against companies for violating the privacy of consumers by sharing sensitive medical information for advertising purposes, the article notes that some of these companies even created lists of people suffering from diseases for the purpose of targeting them with offers for ineffective or worthless cures. Less than a century later, new technologies such as computers, the internet and mobile phones brought with them a flood of newly available consumer information that could be collected and shared for advertising. As computers developed and technologies such as the internet and mobile phones came into existence, the amount of information on consumers that could be collected and shared for advertising increased dramatically.

FTC staff continue to learn from advancements and impacts of technology deployed today. Recent cases show the depth of these advancements:

The Commission issued a complaint against Mobilewalla alleging it used its access to real-time bidding data to harvest consumer information and sensitive location data — including visits to health clinics and places of worship. According to the complaint, Mobilewalla then sold the data it collected to third parties to be used for targeting advertisements and other purposes.

The agency secured a first-ever ban on the use and sale of sensitive location data from Outlogic, LLC, a data broker which allegedly sold consumer location data it collected from third-party apps that incorporated its software development kit (SDK), from its own mobile apps, and by purchasing location data from other data brokers and aggregators.

The FTC alleged that InMarket, another data broker, used consumers’ location data to sort them into particularized audience segments—like “parents of preschoolers,” “Christian church goers,” “wealthy and not healthy,” etc.—which it then provided to advertisers.

These recent enforcement actions underscore the sophisticated forms of surveillance technology embedded within the ad tech ecosystem. The cases also reinforce the relevancy of the 6(b) study’s initial insights, which explores the data types, data sources, and methods of targeting and segmentation that can not only be used to serve ads, but to determine prices as well.

As surveillance pricing continues to mature and deployment spreads, it is important for researchers, enforcers, and policymakers to keep pace. This is why, in addition to making progress on the 6(b) study, the FTC is issuing a Request for Information to invite public comments on surveillance pricing practices and is publishing an Issue Spotlight, discussing some developments and concerns raised in the media, research literature, and other public sources.

Charting the Path Forward for Surveillance Pricing

The FTC has already broken new ground in its approach to quickly evolving spaces like surveillance pricing, but there is much more work to do. The growth of e-commerce means more consumer exposure to prices and discounts that can fluctuate more quickly in online marketplaces. Companies may have expansive and more immediate access to individual consumer data through online channels as opposed to physical stores or print catalogs. Technological advancements can make it less burdensome and less expensive for companies to collect and process troves of data through standard tooling, third-party intermediaries, and machine learning and AI. These advancements point to some key takeaways for enforcers.

First, as enforcers work to root out harmful pricing practices, it is critical to gain a clearer understanding of surveillance pricing. The FTC's new Junk Fees Rule makes clear that when consumers don’t know the price they are paying upfront, harm can quickly follow. The potential harm from surveillance pricing is likewise at its zenith when the pricing of the good or service is opaque and where there are impediments to finding an alternate seller who offers the good or service at a standardized, non-surveilled price. For instance, in the sale of some products – such as cars – consumers often do not learn the true cost of the product until they have invested substantial time and energy. In other scenarios, a seller who uses surveillance pricing could create or take advantage of obstacles that keep consumers from discovering the prices or “discounts” offered by competitors (e.g., using dark patterns to create a false sense of urgency that suggests that the offered price is ephemeral and will no longer be available if the consumer looks at a competitor’s offerings). The Commission’s Policy Statement on Unfairness makes clear that a seller violates Section 5 of the FTC Act when it unreasonably creates or takes advantage of an obstacle to the free exercise of consumer decision making. As surveillance pricing opens new opportunities for unscrupulous pricing strategies, enforcers should stay vigilant.

Second, enforcers must approach surveillance pricing through an interdisciplinary lens. The widespread adoption of surveillance pricing practices threatens to upend the long-standing same-price-for-everyone pricing model that businesses have used for decades. This shift could create ripe opportunities for businesses to engage in deceptive advertising, illegal collusion, civil rights violations, or other harmful practices. At the FTC, staff from our Office of Technology, Bureau of Economics, Bureau of Consumer Protection, and Bureau of Competition are collaborating to examine this shift, ensuring the agency is well equipped to continue protecting consumers and competition.

Third, enforcers must continue to keep pace with fast-moving changes in the marketplace. While surveillance pricing is still relatively nascent, the business incentives to find ways to amass and monetize consumer data are longstanding. Two decades ago, as enforcers argued that the tech sector did not require regulation, Google began harvesting search data to glean insights on its users. Today, that then-budding enterprise has become one of the largest in the world and regulators are only now starting to catch up–reckoning with the impact of this technological shift on kids, fraud, competition, and more.

Today, as relatively nascent surveillance pricing practices evolve, it will be critical to lay out clear principles that guide future developments and enforcement in the space. Once upon a time, individual data collection was restrained by the amount of manual effort it required, and a consumer could just throw away a catalog. In this connected ecosystem powered by algorithms and data collection, every click, every mouse move, and every choice made on the way to every purchase is now catalogued. Enforcers must remain vigilant and ensure that the rules are not stacked in favor of profit at the expense of consumers and fair competition.

***

Thank you to Simon Fondrie-Teitler, Shoshana Wodinsky, and Dan Salsburg who contributed to this piece.