Fans of “Shark Tank” will remember it as one of the show’s most dramatic bidding wars. Charles Yim, CEO of Breathometer, pitched his smartphone-enabled breathalyzer as a way to “help people make smarter and safer decisions” about drinking and driving. All five sharks went for the product hook, line, and sinker. But according to the FTC, the defendants’ deceptive claims about the accuracy of the devices’ readings left consumers floundering.

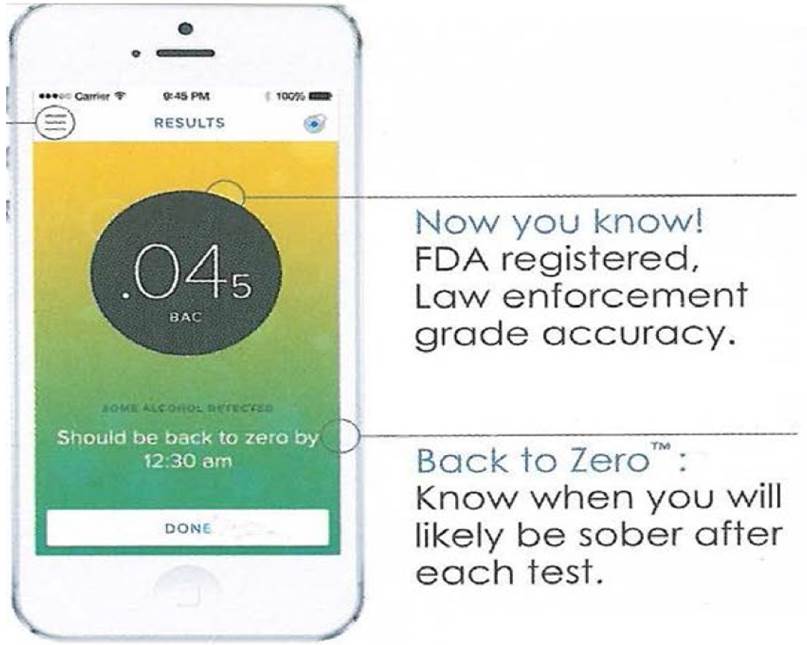

The first iteration of the product, the Breathometer Original, attached to a smartphone through the audio jack. To check their blood alcohol concentration (BAC) before getting behind the wheel, users blew into a small hole in the device. Via an app, their phone would display their purported BAC and “provide guidance on when you will be Back to ZeroTM – or likely sober.” The defendants touted the product as an “FDA-registered device which boasts accuracy that compares favorably to other high-end breathalyzers,” and thus would help consumers determine if they were safe to drive. If not, users could call a cab directly from the app. The company also claimed that the product “has undergone rigorous government lab-grade testing to ensure its accuracy.”

The first iteration of the product, the Breathometer Original, attached to a smartphone through the audio jack. To check their blood alcohol concentration (BAC) before getting behind the wheel, users blew into a small hole in the device. Via an app, their phone would display their purported BAC and “provide guidance on when you will be Back to ZeroTM – or likely sober.” The defendants touted the product as an “FDA-registered device which boasts accuracy that compares favorably to other high-end breathalyzers,” and thus would help consumers determine if they were safe to drive. If not, users could call a cab directly from the app. The company also claimed that the product “has undergone rigorous government lab-grade testing to ensure its accuracy.”

The defendants followed up with Breeze, a Bluetooth-enabled “law enforcement grade product, utilizing a next generation electrochemical fuel cell sensor that has undergone rigorous government lab-grade testing to ensure its accuracy.” According to Breathometer’s Facebook page, Breeze provided “police grade precision” and would detect alcohol levels from zero to .25 BAC.

Except when it didn’t – and that’s the crux of the FTC’s action against Breathometer and Yim.

In late 2014, Breathometer learned of accuracy problems with Breeze. According to the FTC, the results Breeze reported began to experience a “downward drift” – meaning that users had a higher BAC than what Breeze displayed. When it comes to a product that claims to tell people if they’re safe to drive, a device that says users are less intoxicated than they really are is an epic uh-oh.

The defendants tried to fix the problem with math, modifying the app to report a slightly higher number. Then in early 2015, Breathometer conducted tests that turned that initial uh-oh into a full-scale OMG. First, the company learned that ambient humidity and temperature affected results. Second, they determined that Breeze sensors deteriorated significantly over time. But by then, thousands of consumers were basing their decision on whether it was safe to drive after drinking on Breeze’s iffy results.

How did Breathometer respond? According to the complaint, in the third quarter of 2015, the company conveyed a vague message to retailers that it would no longer sell the product, but it didn’t tell retailers – or consumers – why. So as late as February 2016, people could still buy Breeze from big-name national retailers even though Breathometer had known about the inaccurate results for more than a year.

Finally, at the urging of FTC staff, Breathometer sent letters to retailers in May 2016 and email to registered Breeze owners a month later, warning them of the accuracy problem. On October 6, 2016, the company finally disabled the breathalyzer feature of its app and replaced it with a notice to consumers.

The complaint alleges that the defendants made false or unsubstantiated representations about the accuracy of the devices and falsely claimed to have rigorous government lab-grade tests to support what they said. To settle the case, the defendants have agreed to notify purchasers and issue full refunds. In addition, they can’t make any claim about the accuracy of a breathalyzer for making driving decisions unless it’s supported by generally accepted National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) protocols. In addition, the order against CEO Yim prohibits false or unsubstantiated claims about a broad range of products.

Here’s our pitch to advertisers about the significance of the Breathometer case:

Safety claims raise the substantiation ante. It’s usually hyperbole to suggest that companies substantiate their claims as if lives depend on it, but it’s an accurate statement for a product that promises to accurately test the BAC of a person who is deciding whether to drive after drinking. As the FTC said in its Deception Policy Statement, representations about safety are “of great significance to consumers. On this issue, the Commission has required scrupulous accuracy in advertising claims.”

A lot can happen between the drawing board and daily use. Testing in a controlled setting is one thing, but consumers live in the real world – and a wide variety of variables can impact product performance. Your advertising claims should realistically reflect consumers’ actual experience.

Ill-fitting proof doesn’t wear well. It’s a common mistake: A company’s purported substantiation doesn’t “fit” its expansive ad claims. Breathometer said that its Original device would get accurate results for a range between zero and .25% BAC. But in many instances, the defendants allegedly tested for accuracy only up to .02% BAC. It’s important to keep the decimal points straight here: .02% BAC is a world away from .25%, especially considering that a person is typically considered too intoxicated to drive at .08%.

If concerns arise, take early and effective action. In addition to challenging Breathometer’s advertising claims as deceptive, the complaint alleges that the defendants’ course of conduct was an unfair trade practice. According to the FTC, the defendants’ failure to take appropriate action after learning that the device posed a public health and safety risk caused or was likely to cause substantial injury to consumers. That includes people who relied on the device in deciding to drive after drinking – and the rest of us on the road.

In reply to I have not received the by George G