When people seek medical care or visit other sensitive locations, they may think their presence is confidential. Little do most consumers know that if they have their phones with them, their location – for example, at a women’s health clinic, a therapist’s office, an addiction treatment center, or a place of worship – may be collected by tech companies. From there, that uniquely personal data becomes yet another commodity bought and sold in the shadowy information marketplace. An FTC lawsuit against data broker Kochava Inc. alleges that the company acquired consumers’ precise geolocation data and then marketed it in a form that allowed Kochava clients – both subscribers and prospective customers who took Kochava up on a free “sample” – to track consumers’ movements to and from sensitive locations. The complaint charges that Kochava’s conduct is an unfair trade practice, in violation of the FTC Act.

Kochava acquires location data from other data brokers based on information collected from consumers’ mobile devices. Kochava then compiles it in customized data feeds, which it markets to commercial clients eager to know where consumers are and what they’re doing. The amount of location data Kochava has about consumers is staggering. In pitching its products, Kochava offers what it describes as “rich geo data spanning billions of devices globally,” further claiming that its location feed “delivers raw latitude/longitude data with volumes around 94B+ geo transactions per month, 125 million monthly active users, and 35 million daily active users, on average observing more than 90 daily transactions per device.”

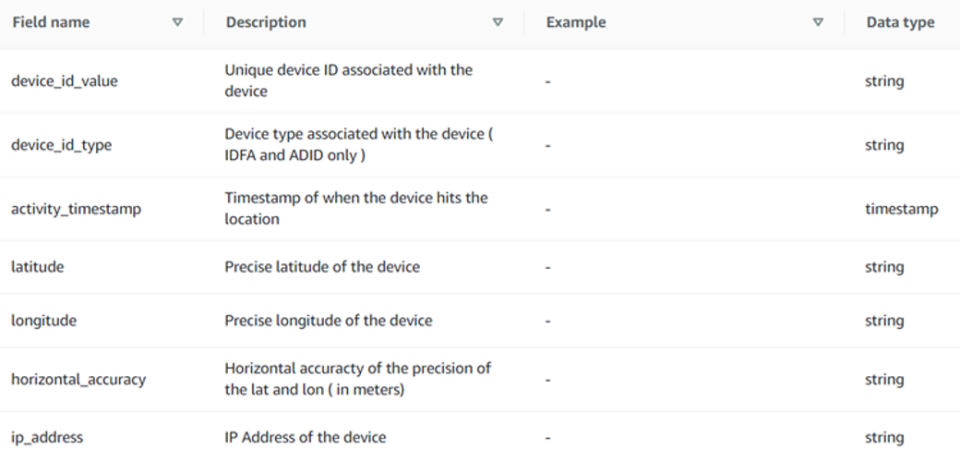

The FTC says Kochava wasn’t kidding in describing both the breadth and the specificity of the data it sells. For example, in the Amazon Web Services (AWS) Marketplace, Kochava used this table to attract new customers:

According to the FTC, Kochava was explaining to prospective clients that its data would link together two key pieces of information for marketers: the timestamped longitudinal and latitudinal coordinates of where a mobile device is located and its Mobile Advertising ID (MAID) – a unique identifier assigned to a consumer’s mobile device. The FTC alleges that Kochava’s location data wasn’t anonymized and, as a result, “[i]t is possible to use the geolocation data, combined with the mobile device’s MAID, to identify the mobile device’s user or owner.”

How do those tech specs translate in the sensitive contexts cited in the FTC’s complaint? It means that Kochava’s data would let customers know that Joe Jones’ cell phone (and therefore Joe Jones) entered a psychiatrist’s office or stayed at a homeless shelter or that Mary Smith visited a center that provides abortion services. According to the complaint, the information could be even more specifically tied to an individual: “[I]t is possible to identify a mobile device that visited a women’s reproductive health clinic and trace that mobile device to a single-family residence. The data set also reveals that the same mobile device was at a particular location at least three evenings in the same week, suggesting the mobile device user’s routine.”

Compounding that concern is the FTC’s allegation that Kochava sold access to its data feeds on publicly accessible information marketplaces and, until just recently, even made free samples available with what the FTC describes as “only minimal steps and no restrictions on usage.” According to the complaint, to gain access to a sample, a potential customer could use an ordinary personal email address and describe their intended use with something as generic as “business.” And let’s be clear: the sample was much more than a smattering. The FTC says it consisted of a seven-day subset of the paid data feed. Converted to a spreadsheet, the sample allegedly filled 327,480,000 rows and 11 columns of data, corresponding to over 61,803,400 mobile devices. According to the complaint, even the free sample included highly sensitive data: “In fact, the Kochava Data Sample identifies a mobile device that appears to have spent the night at a temporary shelter whose mission is to provide residence for at-risk, pregnant young women or new mothers.”

You’ll want to read the complaint for details, but another troubling allegation is that, according to the FTC, “Kochava employs no technical controls to prohibit its customers from identifying consumers or tracking them to sensitive locations. For example, it does not employ a blacklist that removes from or obfuscates in its data set location signals around sensitive locations, such as women’s reproductive health clinics, addiction recovery centers, and other medical facilities.”

From the FTC’s perspective, the injury to consumers is substantial, given that Kochava’s disclosure of highly sensitive information – for example, that a person may be considering an abortion, seeking mental health care, or attending a particular house of worship – could subject them to stigma, stalking, discrimination, job loss, and even physical violence. What’s more, consumers could hardly be expected to take steps to avoid those injuries since they didn’t know Kochava was trafficking in their information in the first place.

The one-count complaint, which is pending in federal court in Idaho, charges that Kochava’s sale, transfer, or licensing of precise geolocation data associated with unique persistent identifiers that reveal consumers’ visits to sensitive locations is an unfair practice, in violation of the FTC Act.

Could someone please provide me with the name(s) of attorney(s) filing class action suit for violation of privacy act??