An anonymous messaging app marketed to kids and teens: What could possibly go wrong? A lot, allege the FTC and the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office. A complaint against NGL Labs and founders Raj Vir and Joao Figueiredo alleges violations of the FTC Act, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA), the Restore Online Shoppers’ Confidence Act (ROSCA), and the California Business and Professions Code. The company also made AI-related claims the complaint challenges as deceptive. The $5 million financial settlement merits your attention, but it’s the permanent ban on marketing anonymous messaging apps to kids or teens that’s particularly notable.

Among the most downloaded products in app stores, the NGL app is named for the text shorthand for “Not Gonna Lie,” but based on the complaint allegations, it could stand for “Not Gonna be Legal.” The app purports to allow users to receive anonymous messages from friends and social media contacts. The defendants expressly pitched it as a “fun yet safe place” for “young people” to “share their feelings without judgment from friends or societal pressures.” For parents wary of their kids’ use of an anonymous messaging app, the defendants assuaged their concerns by touting “world class AI content moderation” that enabled them to “filter out harmful language and bullying.” Consumers who downloaded the app were prompted to create an account that collected a substantial amount of personal information, but NGL didn’t ask how old they were and didn’t use any form of age screening.

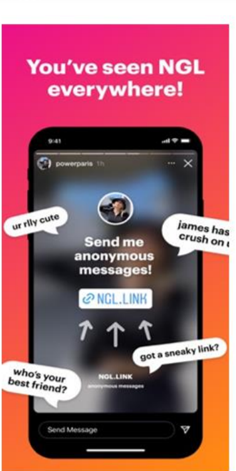

You’ll want to read the complaint for details, but in general terms, app users could post pre-generated prompts to their social media accounts like “Send me a pickup line and I’ll tell you if it worked” or “Share an opinion that’ll get you cancelled” which allowed viewers of the prompts to write an anonymous message in response. In addition, many users received anonymous messages like “are you straight?” “I’ve had a crush on you for years and you still dont know lmao,” and “would you say yes if I asked you out – A.” When a recipient opened the message, a button appeared inviting the person to find out “Who sent this?” with a paid NGL Pro subscription. Eager to learn the sender’s identity, many recipients clicked on that button.

That’s the briefest summary of what NGL told users and parents, but a closer look at the six-count complaint reveals what the FTC and the Los Angeles DA’s Office say was really going on behind the scenes.

The FTC challenges the defendants’ marketing of its anonymous messaging app to children and teens as an unfair practice. According to the complaint, defendant Figueiredo urged employees to get “kids who are popular to post and get their friends to post” and noted that the “best way is to reach out” on Instagram “by finding popular girls on high school cheer pages.” As another NGL executive observed, “We need high schoolers not 20 something[s].” But for any parent of a teenager – or anyone who’s been a teenager – the inevitable consequences of an anonymous messaging app targeting teens wouldn’t be hard to predict. As one high school assistant principal told the defendants, students were using the app to send “threatening” and “sexually explicit content” that was “significantly affecting the mental health and well-being of our students.” According to the complaint, NGL received numerous reports of cyberbullying, harassment, and self-harm and yet chose not to change its marketing strategy or how its product operated.

In addition, the FTC and the Los Angeles DA’s Office allege the defendants used multiple misrepresentations to push their app. For example, many of those anonymous messages that users were told came from people they knew – for example, “one of your friends is hiding s[o]mething from u” – were actually fakes sent by the company itself in an effort to induce additional sales of the NGL Pro subscription to people eager to learn the identity of who had sent the message. But even after receiving numerous complaints describing the anonymous messages as “invasive,” “anxiety inducing,” and “hateful,” NGL’s in-house response was nothing short of gleeful. The complaint cites the following comment from defendant Figueiredo: “These ppl addicted . . . there’s people sharing the [NGL App link] EVERY day and all they get is fake questions 😂.”

The FTC and the Los Angeles DA’s Office say NGL’s promise to parents to protect kids through the use of “world class AI content moderation” proved misleading, too. According to the complaint, the company’s much vaunted AI often failed to filter out harmful language and bullying. It shouldn’t take artificial intelligence to anticipate that teens hiding behind the cloak of anonymity would send messages like “You’re ugly,” “You’re a loser,” “You’re fat,” and “Everyone hates you.” But a media outlet reported that the app failed to screen out hurtful (and all too predictable) messages of that sort.

What’s more, even if users upgraded to NGL Pro, they still wouldn’t be told who sent the message, rendering that claim deceptive, too. But that wasn’t the only problem with the defendants’ practices. According to the complaint, consumers who clicked on the "Who sent this?" button were not clearly told that this was a recurring negative option – not a one-time purchase – and that defendants would charge them $9.99 (and later $6.99) per week for NGL Pro.

The defendants were well aware of consumer complaints about unexpected charges and the ineffectiveness of the “Who sent this?” feature. Even Apple warned the defendants that their product “attempts to manipulate customers into making unwanted in-app purchases by not displaying the billed amount clearly and conspicuously to the users.” How did the defendants respond? In a text discussion with defendants Vir and Figueiredo, NGL’s Product Lead succinctly summarized the company’s reaction to consumer complaints: “Lol suckers.” According to the FTC, the defendants’ use of an online negative option to hype sales of their NGL Pro app violated ROSCA, which requires companies that sell products online with negative options to clearly and conspicuously disclose all material terms of the transaction before obtaining the consumer’s billing information and to get the consumer’s express informed consent before making the charge.

The FTC also says the company collected and indefinitely stored users’ personal data, including their Instagram and Snapchat usernames and profile pictures, information about their location, and their browsing history. The lawsuit alleges the defendants violated the COPPA Rule by failing to provide proper notice to parents, failing to get verifiable parental consent, and failing to provide a reasonable way for parents to stop further use of or delete the data of kids under 13.

The complaint also alleges multiple violations of California consumer protection laws.

The proposed settlement includes a $5 million financial remedy – $4.5 million for consumer redress and a $500,000 civil penalty to the Los Angeles DA’s office. But most importantly, the order bans the defendants from offering anonymous messaging apps to kids under 18. How long will that ban be in place? Forever.

Among other things, the settlement requires the defendants to implement an age gate to prevent current and future users under 18 from accessing the app and mandates the destruction of a substantial amount of user information in the defendants’ possession. In addition, the defendants must get consumers’ express informed consent before billing them for any negative option subscription, must provide a simple mechanism for cancelling those subscriptions, and must send reminders to consumers about negative option charges.

What guidance can other companies take from the settlement?

The FTC will use all of its tools to protect both kids and teens. Certainly COPPA is (and will remain) an important tool for protecting kids under 13 and for ensuring that parents – not tech companies – remain in control of children’s personal information. But this action also reinforces the FTC’s concern about information practices that pose a risk to teenagers’ mental and physical health.

Don’t tout your company’s use of AI tools if you can’t back up your claims with solid proof. The defendants’ unfortunately named “Safety Center” accurately anticipated the apprehensions parents and educators would have about the app and attempted to assure them with promises that AI would solve the problem. Too many companies are exploiting the AI buzz du jour by making false or deceptive claims about their supposed use of artificial intelligence. AI-related claims aren’t puffery. They’re objective representations subject to the FTC ‘s long-standing substantiation doctrine.

There’s nothing “LOL-worthy” about ROSCA violations. For decades the FTC has used both the FTC Act and the Restore Online Shoppers’ Confidence Act to fight back against illegal negative options. According to the complaint, the defendants enticed teens with anonymous questions like “would you say yes if I asked you out” and then presented them with that hard-to-resist “Who sent this?” button without clearly explaining that the company was enrolling them in a negative option subscription and charging them every week. That the defendants used this illegal bait-and-switch tactic against teens and then laughed about it adds brazen insult to the financial injury they inflicted.

What possible good or benefit could derive to people from using this--to adults, to teens, to children--to ANYONE except to line the pockets of the scornful, amoral developers of this horrible technology?